PLASTICS NEWS REPORT

Published: October 29, 2014 9:04 am ET

Updated: October 29, 2014 9:06 am ET

Image By: Rich Williams

The Toxic Substances Control Act, by all accounts, is not a good law. The members of Congress who voted it into existence knew at the time it wasn’t a good law. It’s a paper tiger that is supposed to protect American consumers from harmful chemicals in their homes and workplaces. But tens of thousands of inadequately or untested chemicals were allowed to remain in use after TSCA was enacted in 1976.

And of the approximately 85,000 chemicals that were either grandfathered under TSCA or have been introduced since, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has issued regulations to control only five.

The law requires companies to alert EPA before introducing new chemicals, but it does not include requirements to provide any safety data.

The fact is, the only thing anyone can agree on when it comes to TSCA is that it’s not doing the job.

In the absence of a good, working federal law, over the last more than 30 years, some states have taken it upon themselves to regulate chemicals and products containing chemicals on their own — with decisions sometimes based on science and fact but sometimes not. One of the most famous of those laws, California’s Proposition 65, has also been one of the harshest on plastics and plastics products.

Vinyl products are much maligned in the state thanks to the warning label Prop 65 requires of them, stating they could be harmful to consumers’ health. And the courts finally had to step in to halt California’s repeated efforts to add polycarbonate component bisphenol A to the state’s list of harmful chemicals based on outdated and questionable scientific reports and the lack of proper scientific review.

The patchwork of state laws makes it difficult for chemical producers and plastics processors who use chemicals to do business.

An opportunity for compromise wasted

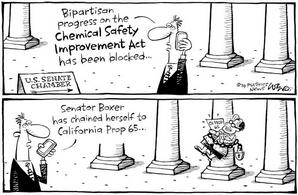

Congress has taken up TSCA reform from time to time over the years, but the process has always gotten bogged down. In May 2013, there was a compromise bill introduced that appeared to have an actual shot at moving forward.

The Chemical Safety Improvement Act was proposed by Sen. David Vitter (R-La.) the top Republican on the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, and the late Sen. Frank Lautenberg (D-N.J.). The measure would have required testing of all chemicals on the market as well as new chemicals, and it would have granted EPA the authority to phase out or ban chemicals deemed harmful.

The bill drew bipartisan support, but it was opposed by Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.), who chairs the Environment and Public Works Committee.

Boxer has made it clear that no chemical regulation reform bill would make it past her committee and onto the Senate floor without major changes. Chief among her concerns is a fear that language in the bill could pre-empt existing state chemical restrictions and interfere with state authority to regulate or restrict chemicals within their borders once EPA acts on those substances.

In other words, she wants to protect Prop 65.

Letting one state dictate chemical policy is bad for commerce, bad for the economy and bad for chemical companies. Unless that state is California, in which case it’s terrible for commerce and even worse for the plastics supply chain. A patchwork of state laws that plastics companies must track, react to and navigate while doing business is bad for business.

A compromise must be reached.

Bolting a bill to the committee room floor until you get everything you want in a completely revamped measure is not compromise.

Compromise is not one person getting everything he or she wants; it’s both sides giving a little to get to a law that, while potentially still imperfect, is markedly better than what the chemical industry and consumers have today.

|